ISSUE 3: High Maintenance

Letter from the Editors

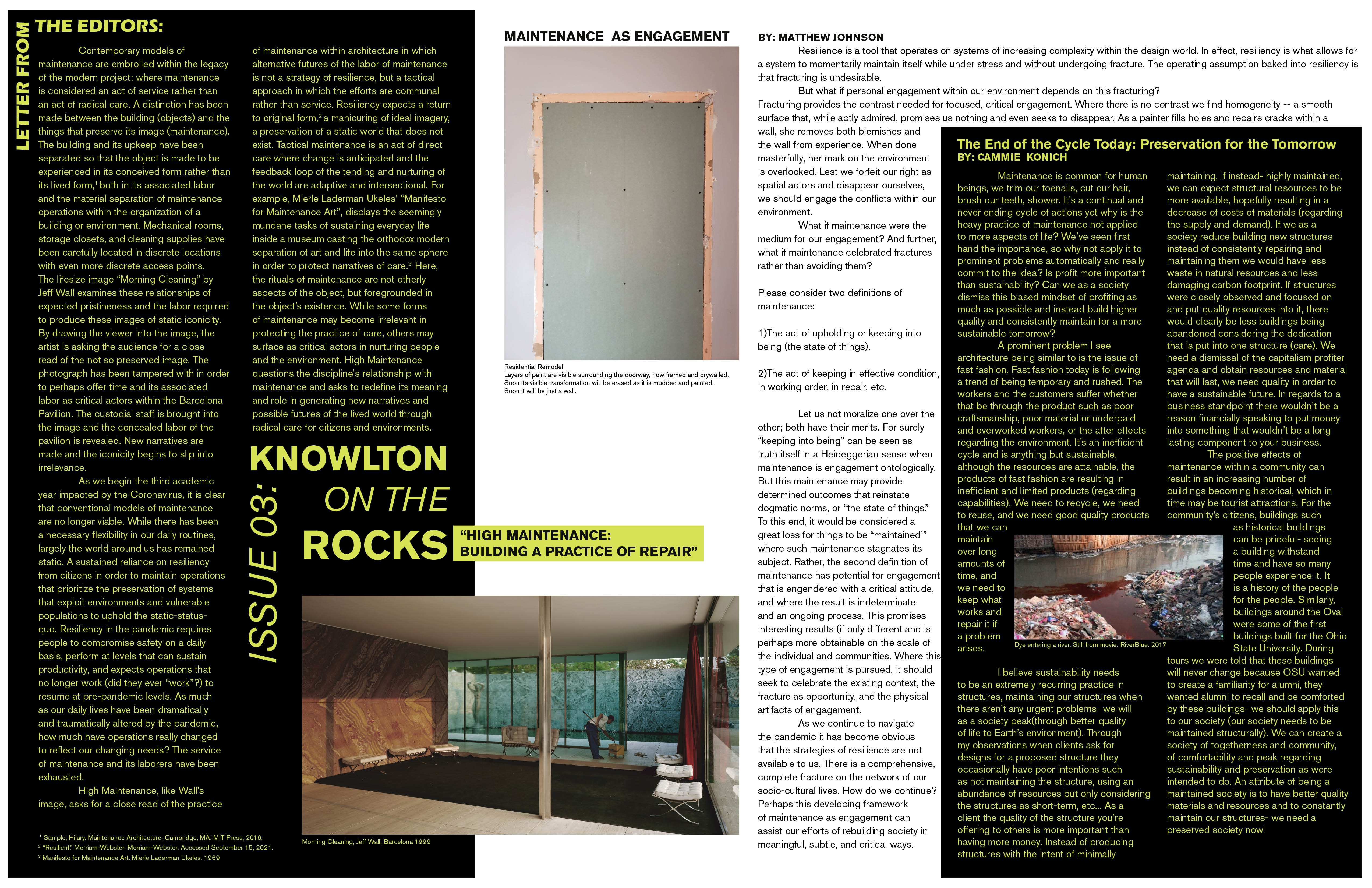

Contemporary models of maintenance are embroiled within the legacy of the modern project: where maintenance is considered an act of service rather than an act of radical care. A distinction has been made between the building (objects) and the things that preserve its image (maintenance). The building and its upkeep have been separated so that the object is made to be experienced in its conceived form rather than its lived form1, both in its associated labor and the material separation of maintenance operations within the organization of a building or environment. Mechanical rooms, storage closets, and cleaning supplies have been carefully located in discrete locations with even more discrete access points. The lifesize image “Morning Cleaning” by Jeff Wall examines these relationships of expected pristineness and the labor required to produce these images of static iconicity. By drawing the viewer into the image, the artist is asking the audience for a close read of the not so preserved image. The photograph has been tampered with in order to perhaps offer time and its associated labor as critical actors within the Barcelona Pavilion. The custodial staff is brought into the image and the concealed labor of the pavilion is revealed. New narratives are made and the iconicity begins to slip into irrelevance.

As we begin the third academic year impacted by the Coronavirus, it is clear that conventional models of maintenance are no longer viable. While there has been a necessary flexibility in our daily routines, largely the world around us has remained static. A sustained reliance on resiliency from citizens in order to maintain operations that prioritize the preservation of systems that exploit environments and vulnerable populations to uphold the static-status-quo. Resiliency in the pandemic requires people to compromise safety on a daily basis, perform at levels that can sustain productivity, and expects operations that no longer work (did they ever “work”?) to resume at pre-pandemic levels. As much as our daily lives have been dramatically and traumatically altered by the pandemic, how much have operations really changed to reflect our changing needs? The service of maintenance and its laborers have been exhausted.

High Maintenance, like Wall’s image, asks for a close read of the practice of maintenance within architecture in which alternative futures of the labor of maintenance is not a strategy of resilience, but a tactical approach in which the efforts are communal rather than service. Resiliency expects a return to original form2, a manicuring of ideal imagery, a preservation of a static world that does not exist. Tactical maintenance is an act of direct care where change is anticipated and the feedback loop of the tending and nurturing of the world are adaptive and intersectional. For example, Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ “Manifesto for Maintenance Art”, displays the seemingly mundane tasks of sustaining everyday life inside a museum casting the orthodox modern separation of art and life into the same sphere in order to protect narratives of care3. Here, the rituals of maintenance are not otherly aspects of the object, but foregrounded in the object’s existence. While some forms of maintenance may become irrelevant in protecting the practice of care, others may surface as critical actors in nurturing people and the environment. High Maintenance questions the discipline's relationship with maintenance and asks to redefine its meaning and role in generating new narratives and possible futures of the lived world through radical care for citizens and environments.

1. Sample, Hilary. Maintenance Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016.

2. “Resilient.” Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster. Accessed September 15, 2021.

3. Manifesto for Maintenance Art. Mierle Laderman Ukeles. 1969.

OCT 19 / 2021